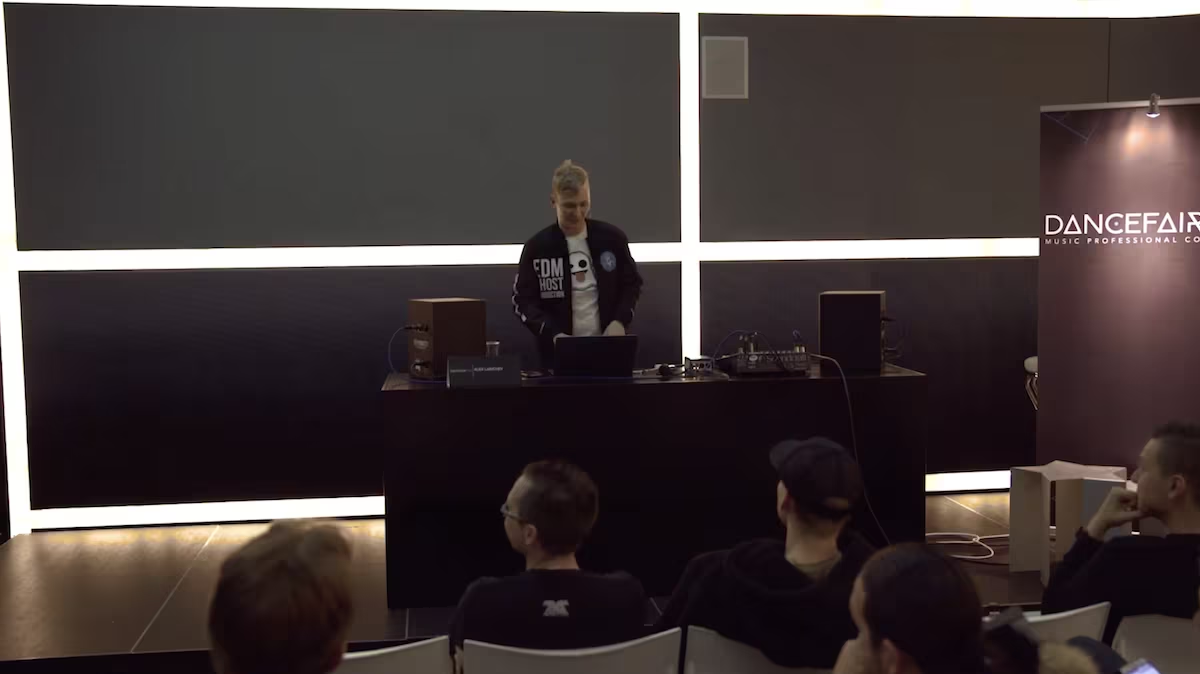

How Music Producers Can Earn Money Without Becoming DJs: Alex Larichev at Dancefair 2019

A roadmap for earning from production without touring, branding pressure, or social media obsession.

At Dancefair 2019, Russian producer and entrepreneur Alex Larichev delivered a talk aimed at a specific audience: producers who love building records but do not want to gamble their future on becoming touring DJs. With about 12 years of experience, releases on labels such as Spinnin’, Armada, and Future House Music, and the founder perspective from EDM Ghost Production, Alex framed the problem in business terms. The dance scene is bigger than ever, but it is also noisier than ever. More competition raises the cost of attention and makes randomness a poor strategy.

Instead of pushing everyone toward the same DJ roadmap, Alex mapped more than twenty three income streams that can be stacked. Some are classic production services, some are product and licensing plays that scale beyond one client, and some are niche markets that most producers ignore until they see demand. The goal is not to abandon releases. The goal is to stop treating releases as the only income plan.

The new reality: oversupply, branding pressure, and why releases are not enough

Alex opens with a hard truth that many producers feel but rarely articulate on stage. Compared with ten years ago, there are simply more DJs and more producers competing for the same festival slots, the same label attention, and the same audience time. That changes the rules of the game. A strong track is still necessary, but it is no longer sufficient on its own. Labels and teams increasingly evaluate the full package: brand story, visual identity, consistency, and the ability to keep attention over time.

He frames this as a choice, not a complaint. If you want the DJ path, you must accept that a large share of your work becomes marketing and visibility. You will spend hours on content, networking, travel, and maintaining an image that stays recognizable in a fast moving feed. Some people enjoy that and are naturally good at it. Others are not, and forcing yourself into that role can lead to burnout, inconsistent output, and weak results. Alex argues that modern success is often about alignment. If your strongest skill is production, it can be smarter to build a business around production, instead of trying to become a public figure first and a producer second.

He connects this to the money reality that most beginners underestimate. A track can be released on a respectable label, chart decently, and still pay very little. Royalties take time, are split across many parties, and depend on performance you cannot fully control. In his own story, he mentions earning a small royalty payment even when a track reached meaningful Beatport chart results. The number is not the point. The point is that releases alone rarely provide stable monthly income for most producers, especially early in a career.

That is why the rest of the talk is portfolio driven. Alex does not say you should stop releasing music. He treats releases as credibility and marketing: proof that you can deliver at a professional level and a way to open doors. But the cash flow should come from offers with clear deliverables. A client pays for a track, a jingle, a sample pack, a template, or a studio session, and you know what you will earn and when you will earn it. This is also where pricing becomes a skill.

He also explains why pricing should be treated as an experiment rather than a fixed identity label. In his own journey, the first offers started low, around 400 euros, because the goal was to get momentum and proof. Later, as demand and reputation grew, pricing moved up, even reaching a few thousand euros for certain types of work. In the end, he recommends a more balanced range for unknown producers, roughly 300 to 700 euros, because it keeps the pipeline active while still being worth the time and allows you to raise rates later when results and reputation justify it.

This framing also explains his emphasis on platforms and systems. If you are unknown, the fastest route to income is to attach your offer to existing marketplaces where customers already search. Later, when you have proof and repeat clients, you can move more volume through your own channels and keep more margin. The message is practical: in an oversupplied market, you win by packaging skills into products and services that buyers actively want, and by stacking several reliable streams instead of waiting for one lucky breakthrough.

High demand services: ghost production, songwriting, and studio deliverables

Alex describes ghost production as the most direct way to turn studio hours into predictable cash flow. In this model, the buyer receives full credits and an exclusive track, while the producer is paid a fixed fee. The platform keeps a commission for curation, marketing, customer handling, and process management, while the producer receives the larger share. Alex emphasizes that the money is real only when quality is controlled. He says his company receives around 20 to 30 track submissions per day but approves only 4 to 5, because the store can survive only if customers trust that every track is competitive.

From there he broadens the idea from full tracks to smaller, repeatable deliverables. Songwriting work can be sold as stand alone tasks: melodies, chord progressions, topline ideas, lyric concepts, vocal arrangements, and MIDI packs. This matters because it lets producers specialize and still earn. If you are strong in musical ideas but weaker in sound design or final polishing, you can collaborate with someone who loves sound design and mixing. Alex mentions co production structures where one producer focuses on musical direction while another handles sound design, mixing, or finishing, and the final credits and royalties can be negotiated as co authorship when the situation allows it.

He highlights real time studio collaboration as the premium tier. Clients pay the most when they get interaction, immediate feedback, and the experience of building something together. This can be in person or remote, but the principle is the same: fast iteration reduces misunderstandings and increases client confidence. The client feels guided. You are not only delivering audio files. You are delivering certainty and progress. Alex says that this “together in the studio” experience can command the highest rates because the buyer values the human part as much as the technical output.

Several other service lanes fit the same pattern. Mixing and mastering can become a dedicated business because many producers prefer to outsource the technical final step to someone who does it daily. Track review and feedback can work if it is detailed and actionable rather than generic praise. Alex stresses that clients pay for specificity: where the arrangement loses energy, why the drop feels weak, what to change in the bass, how to improve transitions, and which techniques to study next. The stronger your ability to explain the reason behind each change, the more valuable the service becomes.

He also points to quick cash services that solve DJ problems. Mashups are a simple example. He says he first thought mashups were pointless, then discovered constant demand from DJs who do not have time or skills to make their own. A mashup can sell quickly for around 100 euros because the buyer wants a ready to play tool, not a philosophical debate about originality. DJ set intros are another growing market. Big artists often open with a one to three minute cinematic intro that includes their name, a voice tag, or melodies from an existing track. Alex’s team produces intros in different themes, cinematic, space, psycho, and clients buy because intros create a strong stage moment.

Jingles and voice tags are presented as accessible if you can record basic audio and process it well. Alex admits he disliked his own voice at first, then learned to shape it with distortion and pitch effects. Once the workflow was clear, he could produce many per day. The point is not that everyone should do ten jingles daily. The point is that some services have extremely clear scope and fast production time, which makes them efficient income streams.

Alex also adds practical risk management. Payment terms depend on reputation. If you are unknown, a demo first approach can reduce conflict and build trust before full payment. If you are established, upfront payment is more realistic.

Scalable products and new markets: sample packs, licensing, and media work

After service work, Alex shifts to income streams that can scale beyond one client at a time. Audio stock libraries are one example. He mentions platforms like AudioJungle because the same track can be licensed multiple times under different usage terms. That contrasts with ghost production, where a track is usually sold once and is gone. Stock licensing can start slowly, but it can become compounding if you build a catalog, understand what customers search for, and keep publishing consistently.

Sample packs and construction kits are presented as one of the most underrated businesses for electronic producers. Alex claims that five construction kits can earn more than a Spotify release with 300,000 streams. Even if the exact comparison changes by genre, the underlying principle holds: products aimed at other producers have clearer buyer intent than listeners. Sample packs also function as marketing. When your sounds live inside other people’s sessions, your name travels with the product, and some of those buyers later become clients for services like custom work, mixing, or feedback.

Templates for major DAWs, such as Ableton Live and FL Studio, are another product lane. Alex warns against copying famous artists or recreating copyrighted work, and he shares a cautionary story about legal trouble from his own past. The opportunity is real, but only if you build original templates that teach workflow, arrangement, and sound design decisions without cloning protected material. A template that explains why things work is valuable, while a template that imitates a hit can be risky.

He also points to markets outside the DJ bubble. During a period in Los Angeles, he noticed demand for energetic electronic music in games such as racing titles and shooters. Film and video production is another opportunity. New film companies often cannot afford expensive licensing from superstar artists, so they prefer custom music that delivers the right mood at a fraction of the cost. For a producer who can work to brief and deliver reliably, this becomes a professional market with recurring demand and clear business expectations.

Alex is also honest about the supply side. Even when tracks are good, many will not sell. He estimates that roughly 60 to 70 percent of submitted tracks can remain unsold due to competition, trends, and quality differences. His platform uses a three month return policy for unsold tracks, which forces producers to think in catalogs and pipelines, not in one lucky upload. If something does not sell, you either reposition it, improve it, or route it into a different channel such as stock licensing, sample packs, or other marketplaces.

Education is another scalable stream when done strategically. Alex mentions teaching and content: YouTube tutorials, paid subscriptions, live classes, and personalized sessions. Free content can work as lead generation if it is genuinely useful, because it attracts producers who later pay for deeper help. During the Q and A, additional ideas were added such as email marketing funnels, Patreon style donations, live streaming with viewer tips, paid tutorial platforms, and live track fixing sessions. These are optional, but they illustrate the same principle: one skill set can be sold as a service, packaged as a product, or taught as a learning experience.

He closes this part of the playbook with a simple system: pick one fast paying service, pick one product that can be sold repeatedly, and pick one acquisition channel where buyers already search. Start on platforms that already have marketing and SEO, then build your own website as a hub when you have proof and demand. The goal is stability through diversification, not perfection through one magical stream.